18 Poster Presentation

Please watch PREPARING YOUR FINAL PROJECT video.

At the end of the semester, you will have the opportunity to present your research as a final project and presentation. What follows provides useful guidance for preparing each. These are only general guidelines. For detailed instructions on the poster and presentation, you will need to attend the scheduled in-class lecture.

Poster

The audience at a poster session is distractible and mobile. Your job in preparing your poster is to grab and keep their attention so that they will stay and take in your message. One study revealed that you have 11 seconds to grab a viewer’s attention. Whether they are engaged will depend both on the attractiveness of your presentation and on how daunting it appears at first glance. The most effective posters are easily digested. Sentences and paragraphs should be short, and type should be large. For viewers who want more information, the poster should provide an entry point to further discussion with the author about the project and the results.

Keys to a successful poster

Know who your audience is! As yours will be diverse (i.e. experts and non-experts), you will need to make a special effort to frame your question and results in an understandable and interesting way.

Be brief! Distill it down…down… down… to the very essence of your project.

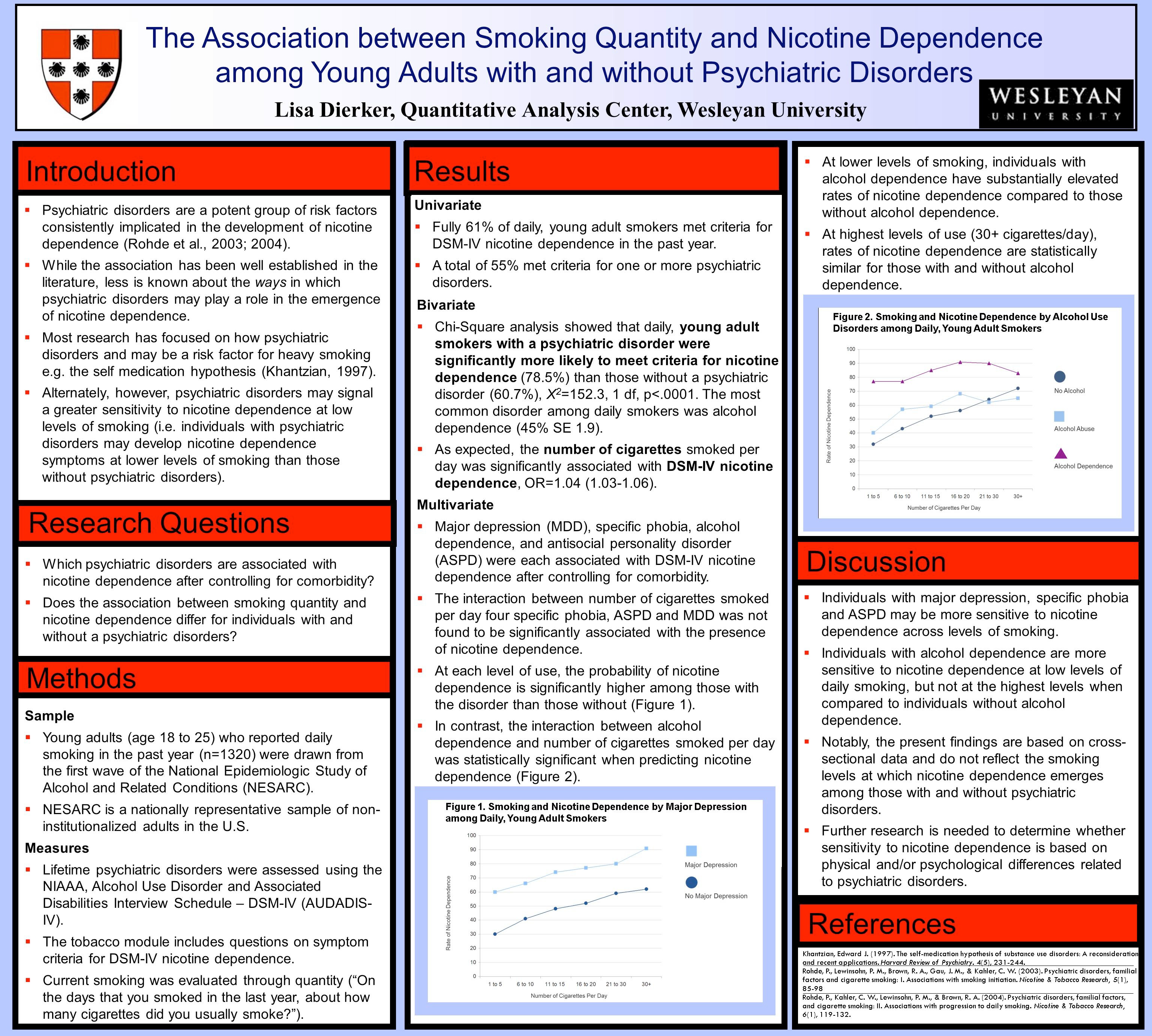

Use figures and graphics where possible. Graphics are good attention-getters. But remember, the golden rule of figures (that they MUST be understandable without reference to accompanying text) applies doubly to posters.

Layout is important! Because text is limited, layout is used to convey the logical structure of your argument. Use columns, boxes, arrows, bulleted lists, etc. to draw your viewer forward through your presentation. Be creative and make the viewing experience intellectually and esthetically satisfying.

Reasons why posters fail

Too much text. Keep each text block to just a few sentences. Large font size will be readable from far away and will help to keep you from using too many words.

Unclear. If you leave out key elements, such as objectives, approach, detailed description of variables or conclusions, people who are not insiders on your subject will not understand what your goal was or why it is interesting. As one recent guest evaluator wrote: “students should be made aware of the technical language that they have grown accustomed to using and should learn to explain in detail the meaning of words such as proxy, gapminder, and other indicators such as poverty headcount ratio, since they are crucial to understanding their study. Not having them explained greatly impaired my understanding of their presentation.”

Poor figures. Some figures are real puzzles, with incomprehensible legends, secret codes, small lettering, cryptic captions, etc. Many spreadsheet and data programs do not produce “reader friendly” graphics (see figures on final page), so you will need to budget extra time to customize your figures so that they are self-explanatory.

Information overload. Most presenters try to do and say too much in one poster. Yes, your research may have yielded many subtle and intertwined results, BUT you will have to settle for one, two, or at most three take-home messages to convey on your poster.

Presenter not present. Remember, the poster is just half of the presentation – you are the other half! Be there, so that those viewers who do find your work interesting will be able to engage you in discussion. Remember, poster sessions are interactive - a truly successful poster is an opportunity for the presenter to gain new knowledge and ideas.

Find your message. Before you begin, try to formulate the essence of what you want to present in a single sentence. This exact sentence probably won’t appear on the poster itself, but it should be your guiding light in deciding what to include and where. Your title and conclusions should be derived directly from this sentence.

Title. Your poster should include a banner title in a large font (e.g. 90 pt.). Below this, put the author(s) name(s) and institutional affiliation(s) in a slightly smaller font.

Body text. Your body text should use a font readable at a distance of at least 4 feet (30 pt).

Introduction. Write a few sentences that identify the problem you address, what is currently known about it (watch out for getting long-winded here!), and your approach to Investigating it. Consider using a bulleted list rather than a text block.

Method. Sometimes, the Method section is included in a slightly smaller font so that those who only want the big picture can skip it.

Results. Select the most pertinent results that support your message. Remove everything that is not absolutely necessary: avoid clutter. Think about the most attractive way to present the data in figures. Avoid tables if at all possible. Each illustration should have a headline title providing a take-home message with a more detailed caption below.

Conclusion. Write the conclusion(s) in short, clear statements, preferably as a list.

Attention-getters. An attractive title is important, but it must be supplemented by attractive graphics. There is no reason why all of your illustrations need to be the same size. Consider enlarging one of these illustrations (or a flow diagram, model, etc. that is the focus of your message) and placing it centrally to attract viewers. You will still need to pay attention to logical flow, directing the viewer’s attention (once you’ve captured it) up to and through this central illustration to your conclusions.

Background. Do not use colored backgrounds or patterns as both are very distracting. Usually, plain white is best. Do use color in your figures in ways that enhance your message.

Get feedback! Ask instructors, TA’s, and/or friends to comment on a draft version. Give yourself a break and review everything with a critical eye. Listen if someone says it’s too complicated – most first-time presenters try to cram far too much into their posters.

Presentation

Reference: <http://www.lifehack.org/articles/communication/18-tips-forkiller- presentations.html> Becoming a competent, rather than just confident, speaker requires a lot of practice. But here are a few things you can consider to start sharpening your presentation skills:

Slow Down – Nervous and inexperienced speakers tend to talk way to fast. Consciously slow your speech down and add pauses for emphasis.

Eye Contact – Match eye contact with the person to whom you are presenting.

15 Word Summary – Can you summarize your idea in fifteen words? If not, rewrite it and try again. Speaking is often an inefficient medium for communicating statistical information, so know what the important fifteen words are so they can be repeated.

Don’t Read – This one is a no brainer, but nervous presenters want to get away with it. If you don’t know your presentation, that doesn’t just make you more distracting, it shows you don’t really understand your message, a huge blow to any confidence the audience has in you. If you need subtle cues or notes to feel comfortable, that’s ok, but don’t’ read.

Speeches are About Stories – Great speakers know how to use a story to create an emotional connection between ideas for the audience. Your research is a story, not just information.

Project Your Voice - Nothing is worse than a speaker you can’t hear. Projecting your voice doesn’t mean yelling, rather standing up straight and letting your voice resonate on the air in your lungs rather than in the throat to produce a clearer sound. The poster session will be noisy. You will need to adjust your voice accordingly.

Don’t Plan Gestures - Any gestures you use need to be an extension of your message and any emotions that message conveys. Planned gestures look false because they don’t match your other involuntary body cues. You are better off keeping your hands to your side.

“That’s a Good Question” – You can use statements like “that’s a really good question” or “I’m glad you asked me that” to buy yourself a few moments to organize your response. Will the other people in the audience know you are using these filler sentences to reorder your thoughts? Probably not. And even if they do, it still makes the presentation more smooth than if you answer were littered with fillers like “um” and “ah”.

Breathe In Not Out – Feeling the urge to use presentation killers like “um”, “ah”, or “you know”? Replace those with a pause taking a short breath in. The pause may seem a bit awkward, but the audience will barely notice it.

Get Practice – Use peers or join Toastmasters (here) to practice your speaking skills regularly in front of an audience. Not only is it a fun time, but it will make you more competent and confident when you need to approach the podium.

Don’t Apologize – Apologies are only useful if you’ve done something wrong. Don’t use them to excuse incompetence or humble yourself in front of an audience. Don’t apologize for your nervousness or a lack of preparation time. Most audience members can’t detect your anxiety, so don’t draw attention to it.

Do Apologize if You’re Wrong – One caveat to the above rule is that you should apologize if you are late or shown to be incorrect. You want to seem confident, but don’t be a jerk about it.

Put Yourself in the Audience - When writing your presentation, see it from the audience’s perspective. What might they not understand? What might seem boring?

Be Entertaining – Presentations should be entertaining and informative. I’m not saying you should be silly or immature. But unlike an e-mail or article, people expect some appeal to their emotions. Simply reciting dry facts without any passion will make people less likely to pay attention.

Have Fun - Sounds impossible? With a little practice you can inject your excitement for your work into your presentations. Enthusiasm is contagious.

Poster Assignment

Submit the title of your poster. Refer to the earlier Writing Chapter for useful tips. (Note: The title that you submit will be used in the formal poster session program).